Jews in the Soviet

Union from 1941

up to the end of the

Soviet era

(Part 6 of 8)

The Right to Emigrate

All pressures on Soviet Jews to forgo their identity do not have the effect the authorities aim for. As Jewish cultural and religious life in the Soviet Union has become practically impossible, and even complete assimilation is no guarantee against discrimination, some Jews start to demand openly the right to emigrate to Israel.

At your left, Jewish "refuseniks"

(who were refused an exit visa) demonstrate in front of the Ministry of Internal

Affairs for the right to emigrate to Israel on January 10, 1973.

At your right,

minutes later, the demonstration (see previous picture) is stopped by policemen.

From the end of the 1960s onward, the samizdat journal Khronika reports about an increasing number of Jews taking part in demonstrations and hunger strikes. Other activities as well testify to the growing awareness of Soviet Jews of their identity and their history.

In spite of the official silence about the extermination of Jews during the Second World War, Soviet Jews start to hold commemorations at sites of massacres during the Nazi occupation. Young Jews with hardly any knowledge of Judaism meet informally at synagogues, closely watched by the KGB, and take part in underground Hebrew lessons.

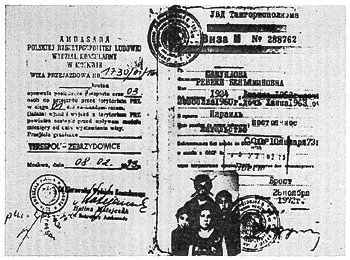

At your left,

This woman received an exit visa in 1973 but was only allowed to take two children

with her. The name of her oldest son and his face on the photograph are crossed

out.

At your right,

group of Jews from Minsk at a Holocaust commemoration in 1975. In front stands

a retired colonel with 15 war decorations. After having complained in 1972 about

the official silence about Jewish resistance, he was demoted, constantly harassed

by the KGB and stripped of his pension. He died of a heart attack in April 1976

after repeatedly being denied the right to emigrate.

It is not long

before the authorities crack down with the arrests and harassment of activists.

By the end of 1970, 44 Jewish prisoners have been sent to labor camps for dissident

activities. News about the trials and the activities of dissidents appear in

the Western media. In many countries solidarity committees are formed. In the

United States, the Jackson-Vanek Amendment of 1973 links trade relations directly

to the question of Jewish emigration. As the issue of human rights is put on

the international agenda, the Soviet government is faced with growing political

pressure.

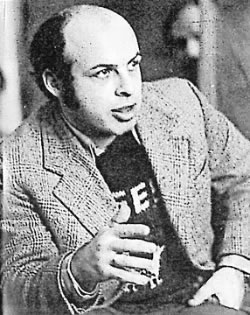

At your

left, underground Jewish theater in a private home; Leningrad, 1982. In the

center Yosif Begun, an engineer who was fired in 1971 after applying for an

exit visa. He was refused permission to earn a living by teaching Hebrew and

was sentenced to exile for "parasitism." Shortly after this picture

was taken, he received the maximum penalty of seven years' prison and five years'

exile.

At your right,

Anatoly Shcharansky, a"refusenik," was arrested in 1978 when the KGB

moved against the Moscow Helsinki Group. Yuri Orlov, the chairman, was also

arrested. Shcharansky was sentenced to three years in prison and ten years'

labor camp.

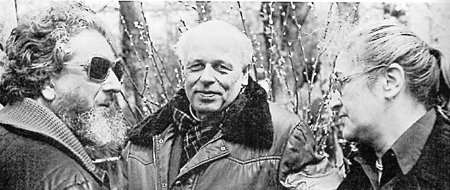

The Sakharovs with Vladimir Slepak, Jewish "refusenik" and member of the Moscow Helsinki Group, just before Slepak was sentenced to five years exile in 1978. For his human rights activities, Andrei Sakharov was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975.

Applications for exit visas usually result in dismissal, followed by months of financial hardship that carries the extra risk of arrest on charges of "parasitism." Nevertheless, from 1971 onward, a growing number of Jews is allowed to leave: 113,800 between 1971 and 1975. These are the years of detente, marked by the signing, in August 1975, of the Helsinki Agreement. The text is published in full in both Pravda and Izvestia. In May 1976, the Moscow Helsinki Group is founded by Yuri Orlov. In the group, Jews and non-Jews cooperate in investigating and publicizing human rights violations.